Other things are possible

On organising labour differently.

Late last year, I had the pleasure of interviewing James Lang, initiator of the Together By Design collective. Officially, this is part 2 of the Design Your Own Career series, but — as with the last instalment — we ended up covering so much more than just James' career story. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Like me, James comes from a design background, so we talk about design skills here — but I can’t help feeling that this conversation is applicable much more widely. There are a lot of industries full of smart, values-driven people; at least some of them are surely wondering, ‘what, this is what I’m spending my life on?’ (This reasoning brought to you by Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber, a book I am reading and hugely enjoying.)

--

KT: With this series, I’m trying to provide a bit of a window into career paths which don’t fit the model of ‘get a job, have a job,’ and I thought that your work, and your pathway into it, would be a super interesting example of this. Can you tell me about the Together By Design project, and how you got from YouTube to there?

JL: Okay, so I’ll probably come at this from a few different directions. I’ll start with the generalisation.

Pretty much everyone I speak to in the world of design and UX feels like there is this existential crisis that’s happening right now. People leave design school with dreams of working on something that’s going to tackle the world’s big problems, like climate change, or social disintegration, or refugee issues, or food crises.

But a small number of organisations have sucked in the talent of the design field to work on a relatively small number of not-that-exciting problems. So you have amazing designers who could be doing so much more than this mundane, reductive work they’re doing, and meanwhile, things like the climate crisis are getting very little attention, actually, from the design industry.

And yet we exist in a capitalist system where you need to have a monthly income, otherwise you’re going to be very vulnerable very quickly.

So, without pretending that the system we live within just doesn’t exist, what can we do to be resilient and flexible as our tiny industry, and the whole system, goes through these convulsions? There are things we can do to try and engage with the limitations of capitalism.

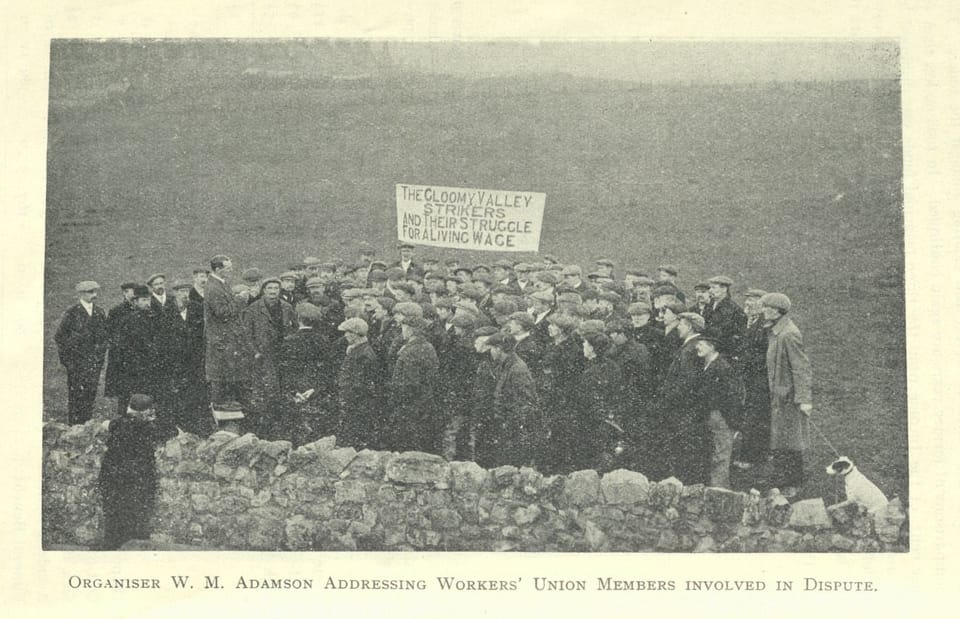

Through history, people have been really creative at looking at different ways that they can organise their labour. Trade unions were an incredibly radical idea, for example. They changed the way that work was organised; now we have an eight hour work day, because of the experimentation and social innovation that was done in that era.

The Quakers also thought about other ways of organising, within the Industrial Revolution, in ways that were more worker-focused and pushed back on forms of labour organisation like slavery. And then more recently, I think collectives are really underused as a way of organising labour.

All I’m trying to say with this is that we look at the current system of ‘you can work for yourself or you can work for a company, and those are the two options’, and there are other ways to do this.

There are other ways to be creative about how you organise labour, and the design industry has not been willing enough to look at some of these possibilities. The ability to use your labour differently, I think, is a really fundamental part of how the world changes.

So anyway, that’s the end of my screed on this subject.

What about your own journey? Where has this screed led you?

I left YouTube about a year ago. I’d got to a point financially where I thought I can afford to live a simple life, I can make choices that are not driven primarily by the need to pay the bills every month.

And I actually saw that as a moment of great responsibility, because it meant that I’ve then got to make really good choices with the time that I’ve carved out. The way that I’ve wanted to do that is to use my time to facilitate other people spending their time in ways that are true to their values, while also respecting that we all need to earn a living.

If you want to work on something that would actually be a reflection of what you believe in, it’s really hard to do. How do you find your fellow travellers? I think you need to have a way of organising people’s spare peripheral time, energy and enthusiasm, into something that’s big enough to make a difference. So I saw that as being what I would do, and I’d identified community as being the topic that I felt I had something to contribute to.

It took me about a year to map out the terrain that could be in scope for this, and then some time to converge it into something that was addressably small. Then people would come to me and say Hey, James, I think what you’re doing sounds really interesting, how do I get involved? And I’d be like, Oh, I don’t know. I didn’t have a way of interfacing people’s enthusiasm with any workable structure.

So where I’ve ended up is that I’ve created a collective that’s called Together By Design. A lot of the inspiration for it was from the world of community building, where some of the technology of organisation — consent-based decision making, collectives, different kinds of anarchist structures — is just so much more commonplace than it is in the UX world, which, while it often has an uneasy relationship with capitalism, is also deeply infused with the thinking of capitalism.

The collective is a labour of love — nobody’s getting paid for it — and it’s really, determinedly amateur. The other thing I wanted to say was about amateurism.

Yes, let’s talk about amateurism.

It’s quite a new phenomenon, this idea that you have a professional designer. The vast majority of design that’s done in the world is done by people who aren’t designers. People tinkering with something to make it work is a tradition as old as time, and that’s how most design happens, right?

The minute that you professionalise a discipline, you institutionalise a lot of the power, a lot of the hierarchies, a lot of the unspoken beliefs about what is and isn’t possible or good practice. You ossify all of that, and you say: If you’re outside of that professionalised tradition, you’re less than.

You have so much orthodoxy baked into the way that fields think about themselves that it becomes very hard for paradigm shifts to take place. And yet, in amateurism, there is no paradigm, you just get started. Things like geology or archaeology wouldn’t exist today if it wasn’t for people who didn’t really know what they were doing, just getting out there and being able to think freely about things.

The word amateur has a bit of a pejorative association, but it comes from the Latin word to love, amare, it’s doing something because you love it, because you’re playing with it and experimenting with it and seeing where it goes.

In the collective, as an amateur, using some part of your time to labour on something you care about, you can avowedly reject some of the professionalism that might be expected of the work you do elsewhere.

I see it as an act of everyday resistance, pushing back on some of the ways in which the production of knowledge has been institutionalised.

Tell me about Together By Design. What is it doing? What are the goals?

There are seven activities. Three inputs, three outputs, and the governance that wraps around it.

The three inputs are gathering stories, play-testing, and the literature review.

I think the design community has really overlooked community as a solution space. If we try and tackle things like social inequality or climate change, or any of the really big important topics of our time, we’re going to need community as part of that mix.

And there’s a lot of really interesting literature that we could all be learning from in other fields, like civic design or social work, or social network theory, or sociology. There’s all this theory that exists that nobody’s got the time to read. So we’re doing that.

So then, the outputs. A pattern library is the first one, of examples of concrete things that people have done to do placemaking or create community, like a phone box with a library in it, or a knitted cover for a lamppost.

The second is a set of design principles. Basically, if the pattern library is the what, the design principles are the how. How do the dynamics of community work? How do you, how should you, how might you maintain the boundaries of a community? How do you onboard new members? How do you deal with transgression? How do you deal with the inevitable life cycle of a community?

Then the third part is talking about it. Social media, conferences, this kind of stuff.

Nobody’s doing all of these things. I’m quite busy on the pattern language and design principles side, and I really don’t want to have much to do with the social media side, but my friend Justine is really all in on the social media side, because that’s what she loves doing.

Do you know what you’re aiming to achieve?

The way that I would judge whether all this is successful or not is threefold. One is, are we actually having fun doing it? That’s really important to me, the joy and the amateurism and the everyday resistance aspect of that. A second bit is, are we creating a conversation in the design industry?

But the most important thing is that we make it easier for people every day to make community where they are. If we make it just 2% easier for people to do this, that would be huge for me.

I would also say that I would be amazed if this doesn’t evolve along the way. At the moment, I’m just trying to have some sense of what the few-years-down-the-line goals might be, and also to hold very lightly the idea of how we get there, because that’s what being in the collective means. Otherwise, I’ve just replicated the power structure of ‘I’ve got an idea, and I’m going to co-opt people to do my idea’. This is about creating a framework for people to coordinate to work on the thing that they care about.

What would you say to someone who was reading this and thinking ‘that sounds brilliant, I wish I had a collective, but how do I do it?’

I guess ask me in a year, because I think I’ll be much older and wiser at that point than I am right now.

But I think the starting point is that you need to have something that actually people are interested in. Does anyone care about this, or is it just me?

And if people are saying yes, are they saying yes because they’re my friends, or because I’m persuasive, or because there’s some power dynamic that I’m not conscious of, or is it an idea that they’re really wanting to commit to? So you need to find ways to make it possible for people to say no to you.

Having a value proposition is really important. You should write it as if everyone’s a volunteer, because if you can create something that somebody would do for no money, then you’ve got something that is genuinely compelling.

And then the third part of it is something I call a beacon event, which is where you find a way to send out a signal that, hopefully, draws people to the thing you’re trying to do.

I think the elements for that are: you need a really concise way of saying what this is; you need to have a way for people to engage with what you’re doing; and you need to indicate in some way that the resources are there to be successful.

When I used to organise music events, I would never put out the beacon signal to other people to co-organise with me until I knew I had a site. Because without a site, it’s just chat. You haven’t got anything.

I’m curious about how your ‘paying the bills’ work is structured. Have there been trade-offs, or are you able to arrange your life so that it feels like mostly you’re working towards the things that you want to work towards?

I’m guessing, from my experience so far, that there is no moment where you say ‘this is perfect and it will always be perfect’.

I think the balance is working quite well, actually, with what I’m doing at the moment, which is that I do one or two days a week of consultancy, and then I’ve got half a day that I dedicate to continuing to learn German and studying, and then I’ve got two and a half days a week to work on the communities project.

Ideally, I’d have a consultancy project that starts in September, that I’d work on all the way through the winter, maybe three or four days a week. Then around the end of April, I’d stop doing that work, and I’d have a whole summer of just doing nice things. The last two years it has worked out like that, and it’s been glorious. But I also recognise that if I find something that doesn’t quite fit that, and it’s really important work to me, I’ll just keep doing it.

And the reason that it works is that my son’s left home now, so he’s self-sufficient. Sally earns money in the theatre, so she’s contributing to what we do. And I was a director of Google, and it pays quite well, and I’ve invested that money in ethical things that I think are worthwhile but nonetheless are sort of an underpinning to all of this.

And it’s an interesting one, because there’s a little bit of, well, here I am critiquing capitalism, but on some level it’s still underpinning my existence here. Why don’t I go and live in a permaculture collective somewhere? And I think that is the moral-logical endpoint of what I’m saying. But also, I don’t feel quite ready to do that.

But it does mean that I can deploy a lot of my time on something that I think is worthwhile. So it’s different, but I don’t think it can ever be perfect.

One more question, and then I’ll stop grilling you. I wonder whether you would like to talk a little bit about the process of leaving YouTube and deciding that you were going to start organising your labour differently, doing your own thing. Was it hard? Was it scary?

I wrote a couple of LinkedIn posts about this recently [ed note: here and here], which might answer your question in a more articulate way than I’m going to be able to here.

But, yes, it was hard and scary. I knew it was going to be hard and scary, and it was still a shock. At the same time, there was part of me — and I don’t know if this is me being a bit of a martyr about it — that thought, ‘one must go through this in order to come out the other side, behold the new me’, or whatever.

I also think that there aren’t clean boundaries to these phases. You have moments of more clarity and more certainty while you’re in the midst of moments of great uncertainty. I don’t think that it ever ends, in a sense, but I think the struggle is generative.

I did have lot of self doubt, worrying about whether I could do this, and whether I have permission to do this. Your inner critic’s voice becomes very strong.

Suddenly you’re on your own in a room with nothing else in it and a blank piece of paper, and the thing I really underestimated is how existentially challenging that is, actually, just to keep going in a way that doesn’t make you question yourself over and over and over again. That’s been the scariest bit, in a way.

What I found is that I would really over-index on the interactions that I had with people. If I had a conversation with somebody, and they were interested in this thing that I was working on, I’d be like, Great! This is the best idea ever! And then I would have another interaction with somebody, and they were just disinterested, not really into it. And I’d be like, Oh, this sucks. I’m an idiot for ever thinking this was a good idea.

I got to the point where I just thought, I have to stop using interactions as a signal of what I’m doing, which ironically means that I have to take even more of it from myself.

You have to believe that what you’re doing is worthwhile, and to summon that from yourself. That, I think, is a lesson it’s taken me a while to learn.

--

Thank you, James, and thank you to Kate for introducing us. As always, talking to smart, interesting people is one of my favourite parts of this work, and I'm grateful to be able to share it with you all.

For a while, inspired by Ross Gay's wonderful Book of Delights, I've been noticing my own delights and writing them down. I shared a few with some friends recently and they said such lovely things, I thought I'd start including one here.

*

May

YESTERDAY’S CHIPS

Two delights for the price of one tonight: first, we - the four of us: me, Ben, Pete and Emma - made the perfect barbecue, by which I mean that by the time we were all pleasantly full there was one piece of courgette and a spoonful of green salad left, which Emma ate later.

And then, as we were sat around the table considering the courgette slice and the nearly-empty salad bowl, Ben happened to glance out of the window and notice the light on the cottages across the road, and Emma looked at the time and said that it was eighteen minutes before sunset – a time we knew because we had missed it the night before, by seven minutes – which gave us time to put on our shoes and find our coats and rush over the common to the cliff edge to watch the sun set over the sea, arms around each other in our pairs, watching the gulls flying in to roost and the colours changing in the sky and the shaft of peach light illuminating the clouds above the sun as it dipped below the horizon and disappeared.

In many ways, the barbecue was not perfect: the wind was very cold, so that we had to eat inside, and throughout the whole thing I had a recently sprained ankle, so that my rush across the common was more of a hobble, but still, the evening contained these two delights as well as many smaller ones: Ben strapped up my ankle with gentle care and Emma and I toasted her new job and there was halloumi on the barbecue, and yesterday’s chips, not that it matters, were perfect.